Baeza und Úbeda, die beiden Städte in der Provinz Jaén, sind sehr Renaissance-geprägt und deren Altstadtteile seit 2003 UNESCO-Weltkulturerbe. Baeza wurde 1226 als erste Stadt Andalusiens durch Ferdinand III von den Mauren zurückerobert.

Baeza and Úbeda, both in the province of Jaen, are very much Renaissance towns and their centresnhave been UNESCO World Heritage since 2003. Baeza was the first Andalusian town to be reconquered from the Moors in 1226 by Ferninand III.

In Baeza können wir die alte Universität mit dem kunstvollen Innenhof nicht betreten, weil gerade eine Trauung stattfindet. Macht nüt, wir fotografieren stattdessen den alten Seat 1500, mit dem der Bräutigam später seine frisch Angetraute „ent-fährt“ und ergötzen uns am ebenfalls oldtimerähnlichen Brautjungfern-Quartett.

Our first attempt to see the old Univeristy building with a elegantly decorated courtyard was blocked by a wedding, but we got the chance to get some pictures of the magnificent Seat 1500 oldtimer the groom was to drive off with his bride as well as of the bridesmaids that also looked a bit old-timey.

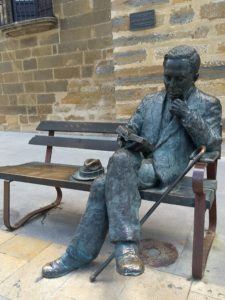

An der Universität hat der Dichter Antonio Machado unterrichtet. Sein Denkmal erinnert uns an den Leitspruch unserer Reise

This university also had the poet Antonio Machado as a teacher, a monument to him reminds us of the motto of our journey.

Natürlich besuchen wir auch hier die Kathedrale, die uns stark an jene Jaéns erinnert. Sie ist eine Mischung aus Gotik und Renaissance und wurde Mitte des 16. Jhts. von Vandelvira entworfen resp. wiedererrichtet. Der tonnenschwere Leuchter in der Gebäudemitte wurde erst in den 1980-er-Jahren aus Jaén gebracht.

A must see in Baeza was the Cathedral, that strongly reminded us of the one in Jaen. A mixture of Gothic and Renaissance, designed and (re)built in the middleof the 16th century by Vandelvira. The central chandelier, weighing several tonnes, was brought to Baeza from Jaen in the 1980s.

Baeza ist wie Úbeda sehr gut erhalten und bietet Sehenswertes: einen Schlachthof aus dem 14. Jht. (heute Verwaltungsgebäude) oder einen badenden Hund – „er liebt den Schaum in Gesicht“. Nein, zwischen den beiden Bildern besteht kein direkter Zusammenhang.

Baeza is like Úbeda very well preserved and offers a lot to see, a old Slaughterhouse from the 14th century (now a public building) or a bathing dog -„he loves foam in his face“-. And no, there is no direct relation between the two pictures.

Wir biegen ihn ein Seitengässli mitTapas-Bars und Restaurants ein, in denen fast ausschliesslich Spanier*innen sitzen. Gutes Zeichen. Beim letzten Sonnenschirm unterhalten sich zwei Personen, der ältere Herr grüsst mich, sobald ich auf seiner Höhe bin. Wo ich/wir herkomme/n, fragt er,. Zwei, drei Worte, und der Mann will uns etwas zeigen. 5 Schritte, er öffnet ein grosses Tor zu einem langen Haus und bittet uns einzutreten. Fernandito – „so nennen mich hier alle“ – ist 83. Er war Bauingenieur, sein Grossvater und Vater waren wohlhabende Olivenölhändler. Das Haus mit dem Wehrturm diente als Lager. Fernandito und seine beiden Brüder haben das gesamte Gebäude geerbt und jüngst umbauen lassen. 3 Familien leben nun dort, die Ehefrau unseres „Gastgebers“ dürfen wir ebenfalls begrüssen. Der Turm mit Stadtor (torre de los Aliatares (muslimisches Stammesvolk?)), ist der letzte erhaltene Teil der Ringmauer aus dem 12. Jht. „Das zeige ich nur Leuten, die mir sympathisch sind“. Wir fühlen uns schon ein Bisschen geschmeichelt.

We turn into a narrow street with tapas-bars and restaurants where all the patrons look spanish, a good sign. Under the last parasol a elderly gentleman is talking with a woman, and he greets me as I reach him. He asks where we come from, and after exchanging some words he tells us he wants to show us something. A few paces away he opens a big heavy door and lets us into a big cavernlike room with beautifully hewn stonewalls. He introduces himself as Fernandito -„that’s what everybody calls me here“- he is 83 and has been a civil engineer, his father and grandfather were well-to-do olive oil merchants. He has inherited the stately house together with his two brothers and they have turned it into nice appartments with all modern comforts and with the medieval walls still visible. We get to enter the Torre de los Aliatares, the last remaining tower in the muslim city wall and a very impressive constrution that „normal“ tourists only get to see from the outside. „I only show this to people I think are nice“, Fernandito tells us. Yes, we do feel honoured.

Zum Abschied erklärt uns Fernandito mit Nachdruck, wo wir nicht essen sollen, weil trotz grosser Portionen zu teuer, und wo wir jedoch unbedingt essen müssen, weil lecker und anständige Preise…

As we leave, Fernandito insists on tell us where not to go for lunch, as their portions are too big and not very good, but rather some other places where the food is delicious and the prices fair.

In Úbeda überrascht uns die Hl. Erlöserkappelle, im dem 16. Jht. von den Architekten de Silhoé und Vandelvira geplant. Sie ist die Privatkappelle von Francisco de los Cobos, dem Staatssekretär Karls I resp. V. Wenn Funktionäre Macht demonstrieren…

In Úbeda we are surprised by the sumptuous Chapel of the Saviour from the 16th century, designed by the architects Silhoé and Vandelvira. It was the private funeral of Fancisco de los Cobos, Secretary to Charles I / V and he did show how mighty anad wealthy his family was with this building.

Die Kappelle ist einer von zahlreichen Reinaissance-Bauten und birgt interessante Geheimnisse: Das hölzerne Altarbild verbrannte während des spanischen Bürgerkriegs (1936-39) fast komplett – die Christusstatue blieb verschont und ist heute Teil des neuen Hochaltars.

The Chapel is one of many Renaissance buildings in the town and has a lot of interesting and secretive details The wooden altarpiece was almost completely burnt down during the Spnish Civil War (1936-39), only the central figure of Christ survived and is now part of the reconstructed altar.

Den hölzernen Haupteingang ziert ein Sandsteinbogen, in den die klassischen Götter eingemeisselt sind – absolut ungewöhnlich für die Renaissance und begründet mit der „liberalen Phase“ Karls I / V. Kurz danach regierte wieder der strenge Katholizismus.

The wooden entrace door is decorated by a sandstone arch that shows classical greek gods – remarkable for a church even in the Renaissance and a show of the „liberal Phase“ during Carlos I/V’s reign, which didn’t last long before returning to strict Catholic orthodoxy.

Dem Bürgerkrieg fiel auch die Orgel zum Opfer. Sie wurde neu gebaut und in die restaurierte Kirche eingefügt, war aber leider zu hoch. Deshalb musste ein Teil des Balustraden-Geländers weichen. Dafür singt jetzt auch der Kirchenchor wieder…

The organ was also a vitim of the Civil War, a new one was added after in the restored church, but it was too high for the railings and a section had to be removed. But now at least a chuch-choir sings regularly.

Am Abend geht ein Gewitter über der Stadt nieder. Wasser spielt auch eine zentrale Rolle bei der „Sinagoga del Agua“, die wir besuchen und trocken bleiben. 2007 wurden beim Umbau mehrerer Wohnhäuser die Ruinen einer bis dahin unbekannten Synagoge entdeckt. Der Mikwe, das Bad für die rituelle Reinigung, liegt direkt unter der Synagoge und ist vollständig erhalten, mit 7 direkt in den Fels gehauenen Stufen und mit sog. lebendigem Wasser.

A storm rolls over the town in the evening, rain starts falling. Water was also very important in the Sinagoga del Augua, the Water Synagoge, that we visit to stay dry. It was a completely unexpected discovery made in 2007 as block of houses in the old town was being rebuilt. The Mikveh or ritual bath has been completely conserved with the seven steps hewn directly into the rock and filled with living water.